An updated, expanded, roughed-up version of an article printed in the November 2016 issue of NET Magazine.

How do people understand their worlds?

When people draw pictures in their head, what do those pictures look like?

What is the stuff of mental models?

What is the stuff of thought?

Ruh-roh…shit just got deep. But wait, don’t go anywhere! If you design digital products that people have to use and navigate, considering these questions might revolutionize the way you work.

***

For over three years, I’ve been teaching something that I call Object Oriented UX (OOUX). In a nutshell, it’s the practice of defining a system of objects before jumping into task flows and interaction design. Developers who code in object-oriented languages have been “thinking in objects” for decades.

By contrast, most UX designers are still thinking procedurally. We draw storyboards based on use cases. We concern ourselves with actions before considering the things being acted upon. We might design the interactive flow for “create new recipe” before we design the object — the recipe. The structure of the recipe (its content elements, metadata, and the prioritization of those elements) is at risk of becoming the haphazard result of interaction design instead of the intentional product of sound information architecture.

When UX designers focus on the procedures and skip over object design, it’s a sad day. It causes a disconnect between disciplines. It hampers the creation of elegant modular systems. But most of all, ignoring object design can result in a very confused end-user. As it turns out, it’s not just developers who think in objects. According to my research, object-based thinking is part of human nature.

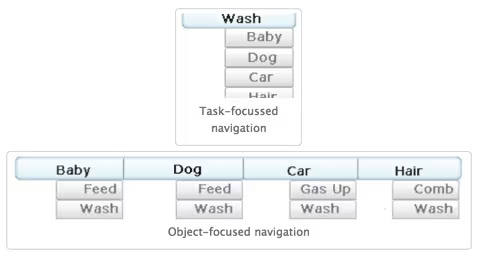

In 2012, Everyl Yankee wrote a post entitled Object-Focused Design. She asked, when you wake up in the morning, what mental model makes the most sense?

Well, I’m not sure about the baby part, but overall I agree with Ms. Yankee when she writes “…users are thinking noun-verb, not verb-noun.” Her concise four points on how to design in objects pretty much sums up my entire crusade:

Navigation is centered around objects — nouns, not verbs

Objects are always the primary representations in the UI

Actions (verbs) performed on the objects comprise the tasks

Tasks are secondarily represented by actions on objects

If you are already convinced and simply want a methodology for designing in objects, I’ve got you here. But if you’re still skeptical (or just interested), read on to see what I’ve dug up on thought, communication, understanding, and perceptions…and how it’s all object-oriented.

THOUGHT IS OBJECT-ORIENTED

According to psychologist Lynda L. Warwick, PhD, author of The Everything Psychology Book, units of knowledge are the “components that work together to process information and create a thought.” She goes on to explain that

The first unit of knowledge is the concept. This is basically a category that groups together items with similar characteristics or properties. These building blocks are used to create the foundation of thought.

A concept may be a concrete object like a “football,” an abstract idea like “a winning goal,” or an even activity like “kicking.” We objectify abstract ideas and activities by creating what psychologists call prototypes: a mental snapshot of a winning goal or a mental GIF of a kick.

Concepts are our headspace-objects. We define them, prototype them, and categorize them. Procedures, like a complex defensive play, are made up of objectified concepts, the relationships between the concepts, and strings of actions taken upon the concepts. Good luck explaining your sportsball strategy to an athlete that does not have a clear grasp on the nature of the ball, the goal, the other players, or the relationships between them.

COMMUNICATION IS OBJECT-ORIENTED

Public service announcement: next time you try to learn a new language, think about loading up on nouns first. Gabriel Wyner, one of the world’s top language-learning gurus and the author of Fluent Forever writes,

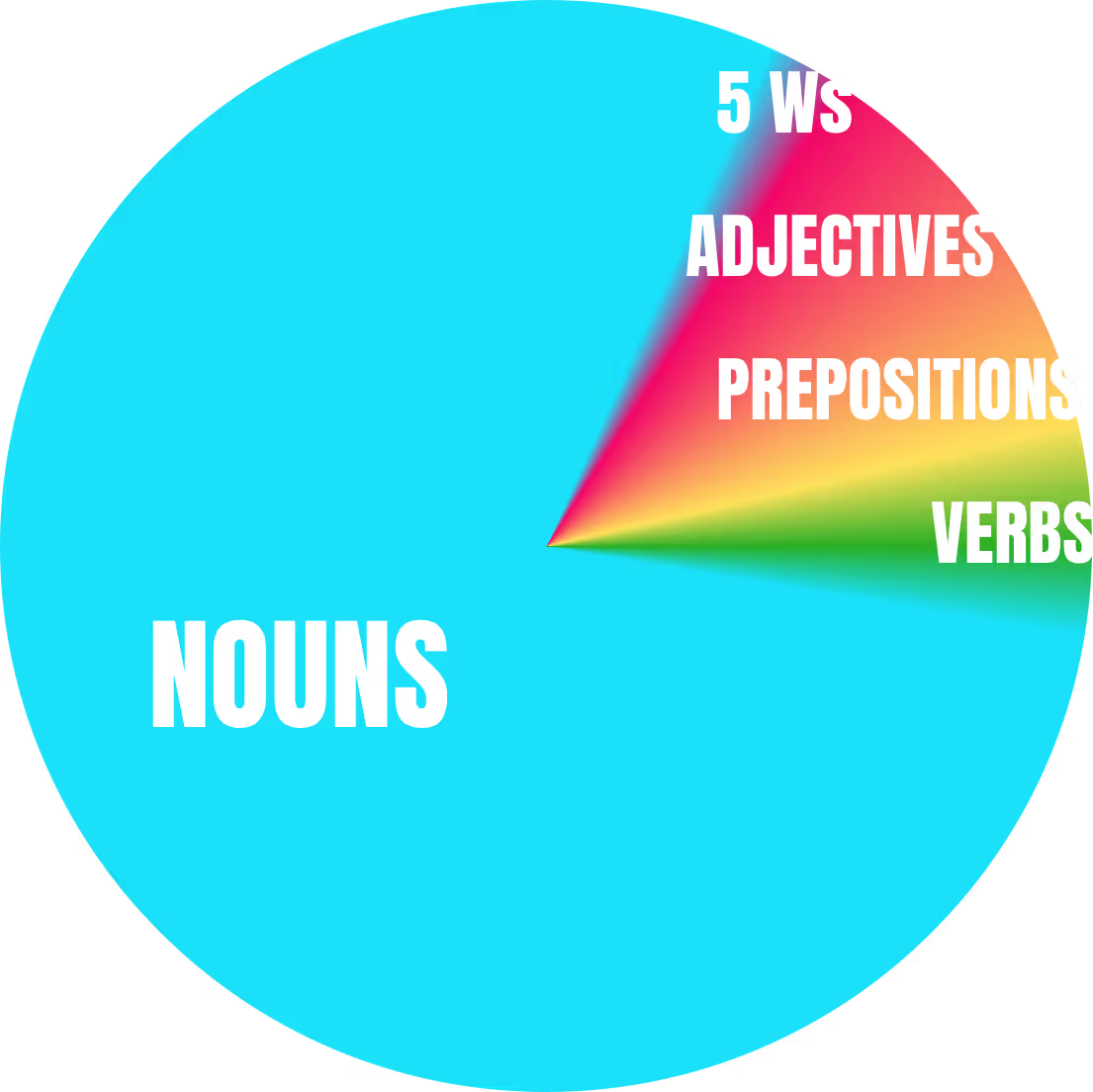

“We prioritize and store concrete concepts because they engage more of our brain, not because they are necessarily any more important…We have no problem naming things; nouns comprise the vast majority of the 450,000 entries in Webster’s Third International Dictionary.”

Even more telling, if you look at the 600 most commonly used words across any language, approximately 80% of those words will be concrete nouns. Imagine going to a foreign country and TSA only lets you through security with 600 words. Would you rather bring all nouns or all verbs? If you brought only verbs: swim, go, live, die, travel, cross, drive, marinate…you’d be hard-pressed to get any point across. Imagine trying to order off a menu or get directions! But what if you packed only nouns? You’d do pretty well with the 600 most common nouns! Eggs and bacon. Bathroom!? Stairs? Tickets!

Better still, learn 500 common nouns, about 60 adjectives to describe those nouns (hot/cold, big/small, pretty/ugly, numbers 1–10), about 25 preposition to position those nouns (in, on, under, behind), the five W’s words (who, what, where, when, and why), and finally, the full conjugations of these “top 10” verbs: be, have, do, say, get, make, go, know, take, see.

Babies know to start with the nouns. As they learn to speak, they get right on labeling objects. With their handful of nouns, they can effectively begin to communicate concepts. Just by saying “truck!” they let you know, “I hear a truck driving by the house!” And stringing together several more nouns can communicate complex concepts. “Doggie ball yard!” effectively conveys, “I’d love to go outside into the backyard to play ball with our dog.” Of course, children will learn a few verbs and the inevitable “no!” in their early years of speech, but the majority of their communication will be in concrete, objectified concepts.

UNDERSTANDING IS OBJECT-ORIENTED

Child psychology can help us gain insight into not only the fundamentals of communication, but also into the fundamentals of understanding. If we look at how freshly-minted humans learn to understand their new world, we can draw parallels into how adult humans learn to understands any new system.

In a way, learning to understand is actually a process of learning to understand objects in increasingly complex ways. The work of Jean Piaget, the renowned child psychologist who defined the most critical stages of development, points to the fact that before children can understand procedures, they must lay some object-oriented groundwork.

The first line of business for a baby is to learn the compelling truth that there are objects. This may sound ridiculously self-evident, but let’s think about it. A baby spend the first nine months of its existence in a world where everything is them. When she, let’s call her Grace, exits the womb, she does not yet understand that the world she sees is not a part of her. For her, it’s just a larger and more complex womb. She must now learn that that mom/bottle/crib are separate entities and separate from her. As Grace learns this, she experiences that traumatic shift that we call separation anxiety.

Next, Grace learns that objects do not cease to exist just because she cannot see them. Object permanence alleviates separation anxiety. Dad went into the kitchen, but that doesn’t mean he has disappeared from the world. Maybe complete hysteria is not in order.

Armed with the knowledge that there are objects and that they exist beyond her immediate perception, Grace can start to categorize them. The first categories she creates? Food and not-food. As she tests objects for edible properties, she’s working on sorting out these two critical categories. Within a few years, she’s realizing that the tiger at the zoo is sort of in the same category as Mittens at home. But Grace is still making all sorts of mistakes as she practices assimilation (adding new things to existing categories) and accommodation (creating new categories for new things). All round things might go in the “ball” category, including the moon and dinner plates.

Around six years old, Grace gains more advanced object perception skills, like social perception, the ability to see an object from others’ perspectives. She’s also getting better at creating categories within categories (hierarchies). But Grace still can’t grasp procedures more involved than a simple cause and effect.

It’s not until about seven or eight that Grace will start to move into the concrete operational phase, in which she can understand multi-step procedures. Simple arithmetic, stories with plot lines, and strategy games come within her grasp. This new operational thinking is built on that foundational understanding of objects.

PERCEPTION IS OBJECT-ORIENTED

Jennifer Groh, professor of Neuropsychology at Duke University, postulated in her book Making Space that “nine tenths of brain power is spent figuring out what and where things are.” Her research has led her to believe that “perhaps the brain’s systems for thinking about space are also the brain’s systems for simply thinking.”

Indeed, the majority of our brain’s processing power is used to categorize information gathered from our senses into our perceptual reality. Our brains find edges, make shapes, place those shapes in space, and relate shapes to one another. We look for continuity, closure, proximity, layering, and relative size — and convert all of that information into objects and the relationship between them.

DESIGN SHOULD BE OBJECT-ORIENTED, TOO

When we create a new product or service, we want to empower people to be able to take a new action in a new or novel way. Design is all about improving the way people get things done, right? So it’s understandable that as UX designers, we’d focus on the getting done.

But for any process to be understandable, it must be built atop an established object-based mental model. As mentioned previously, for an athlete to understand coach’s defensive play, she must first understand the ball, the goal, the other players, and the relationships between all of these objects in her “problem domain.” This seems obvious, but how many times have you stepped into a new digital environment that expected you to start taking action before you had a grasp on the things within that environment? Confusion arises within our products when users attempt to navigate tasks without being able to get firm grasp on the objects that underpin those tasks.

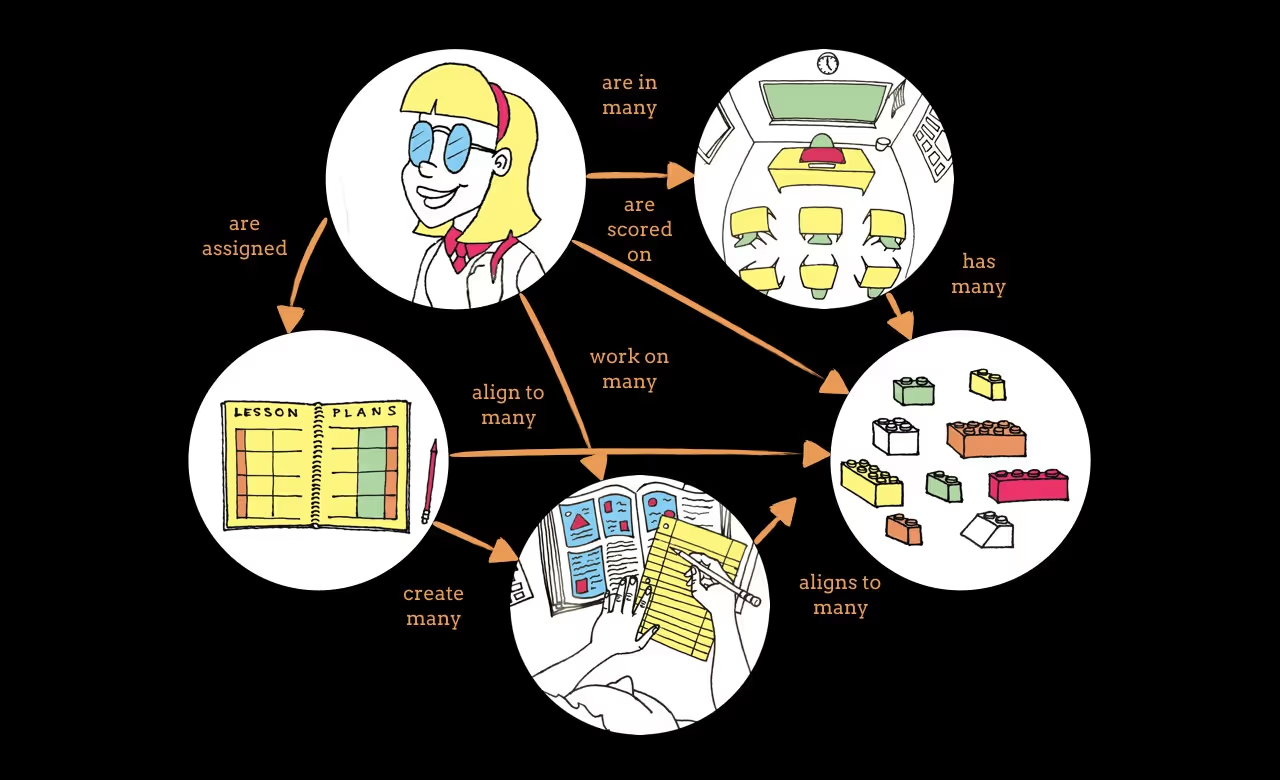

When real world objects align with digital objects

Imagine a teacher as she opens up a new app. Within moments, she can see students, classes, lesson plans, homework assignments, and standards — the main things that make up her world. In the app, all these things seem to relate to each other just as the do in real life: students are part of classes and lesson plans align to standards. It all makes sense. She’s not using a bunch of processing power trying to untangle what the things are. The system is reflecting her reality, therefore she can confidently move on to getting things done within the app. On familiar and comfortable ground, she’s ready to dive into whatever revolutionary functionality this new app has to offer.

Just as an object-oriented design is easier to translate into object-oriented code, an object-oriented design is easier to translate in an object-oriented user headspace. When our users can clearly perceive, name, and categorize the objects within the systems we design, they can quickly move onto actually using the system. Designing “objects-first” is not about demoting actions. On the contrary, OOUX clears the way and sets the stage…so your interaction design and functionality can shine.

** “All” is a strong word. I am currently looking into some interesting research on the differences between how westerners and easterners understand and articulate their world. From what I can tell, westerners are much more object-oriented than easterners! While westerners look for edges and individual units, easterners seem to think more in harmonies and cycles. More on this to come!

---

Originally published on Medium